The Habit You Keep Breaking Isn't the Problem. The Trigger Is.

You're not failing because you lack discipline. You're failing because you haven't identified what's actually setting off the behavior.

You've tried to change this habit before. Maybe many times. You committed, you started strong, and then somewhere along the way it fell apart. Again. The conclusion feels obvious: you lack discipline. You're not consistent enough. You need to try harder.

But what if the habit itself isn't the problem? What if you've been troubleshooting the wrong part of the system?

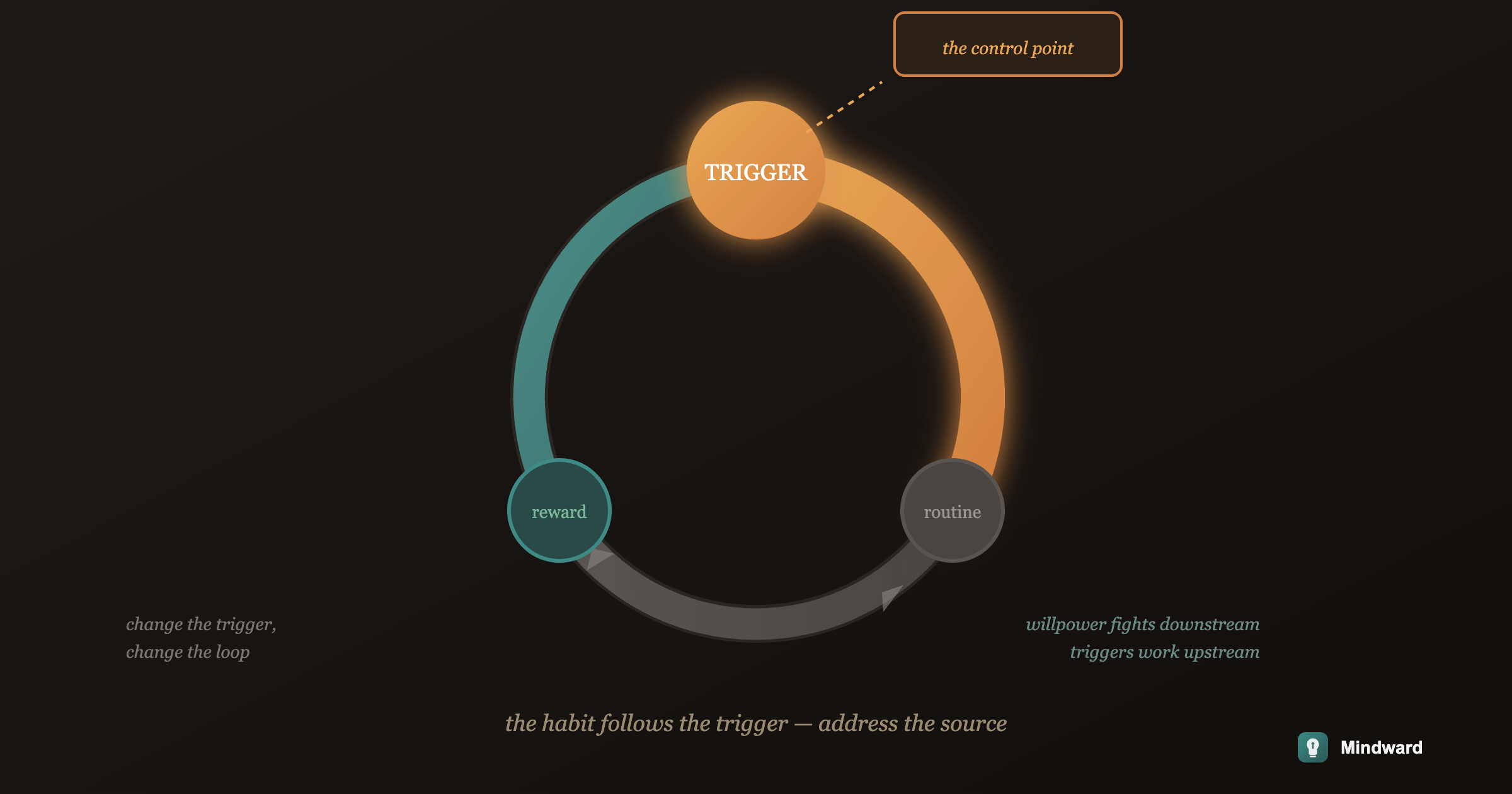

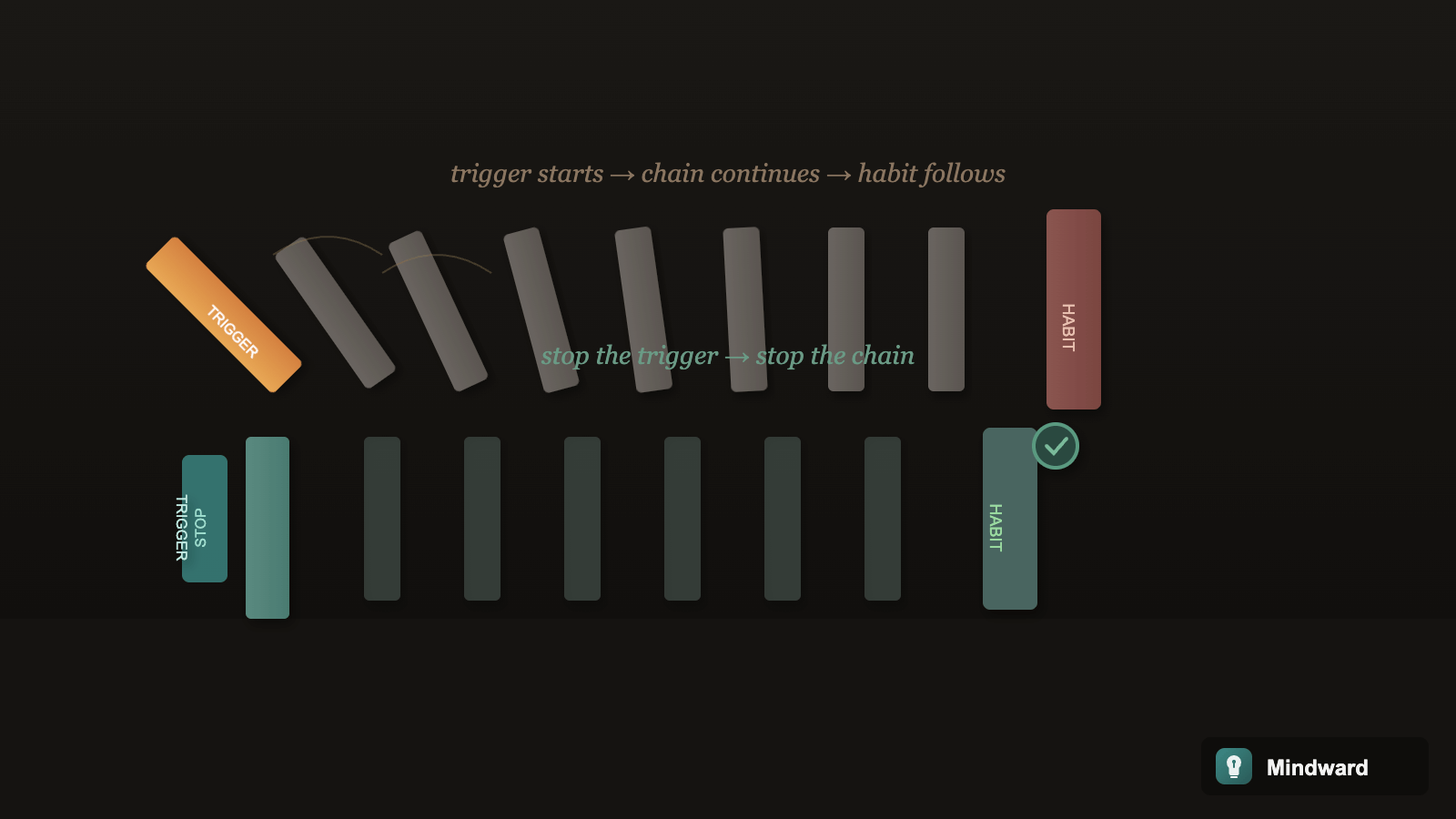

Every habit has a trigger—the cue that sets the behavior in motion. When that trigger fires, the habit follows almost automatically. If you keep breaking the same habit, the issue usually isn't your commitment to change. It's that you haven't addressed what's triggering the behavior in the first place.

How Triggers Actually Work

Triggers aren't just reminders. They're neurological shortcuts. When a cue appears—a time of day, an emotion, a location, a preceding action—your brain doesn't deliberate. It runs the program. This is efficient for good habits and devastating for bad ones.

The trigger might be obvious: you open your phone and end up scrolling. Or it might be hidden: you feel anxious, so you reach for food. The behavior that follows feels like a choice, but by the time you're aware of it, the trigger has already done its work.

This is why willpower fails so often. You're trying to interrupt a process that's already in motion. By the time you're fighting the urge, you've already lost ground.

Finding the Real Trigger

Most people can name the habit they want to change but can't name the trigger that starts it. This is the gap. Until you know what's cueing the behavior, you're fighting blind.

Triggers typically fall into five categories: time, location, emotional state, other people, and preceding actions. When you catch yourself in the unwanted behavior, ask: What time is it? Where am I? How am I feeling? Who's around? What did I just do?

Patterns will emerge. Maybe you snack when you're bored, not hungry. Maybe you procrastinate after checking email. Maybe you lose your temper when you're tired. The behavior isn't random—it's responding to something specific.

You can't change a habit you don't understand. And you can't understand a habit until you understand its trigger.

Redesigning the Trigger

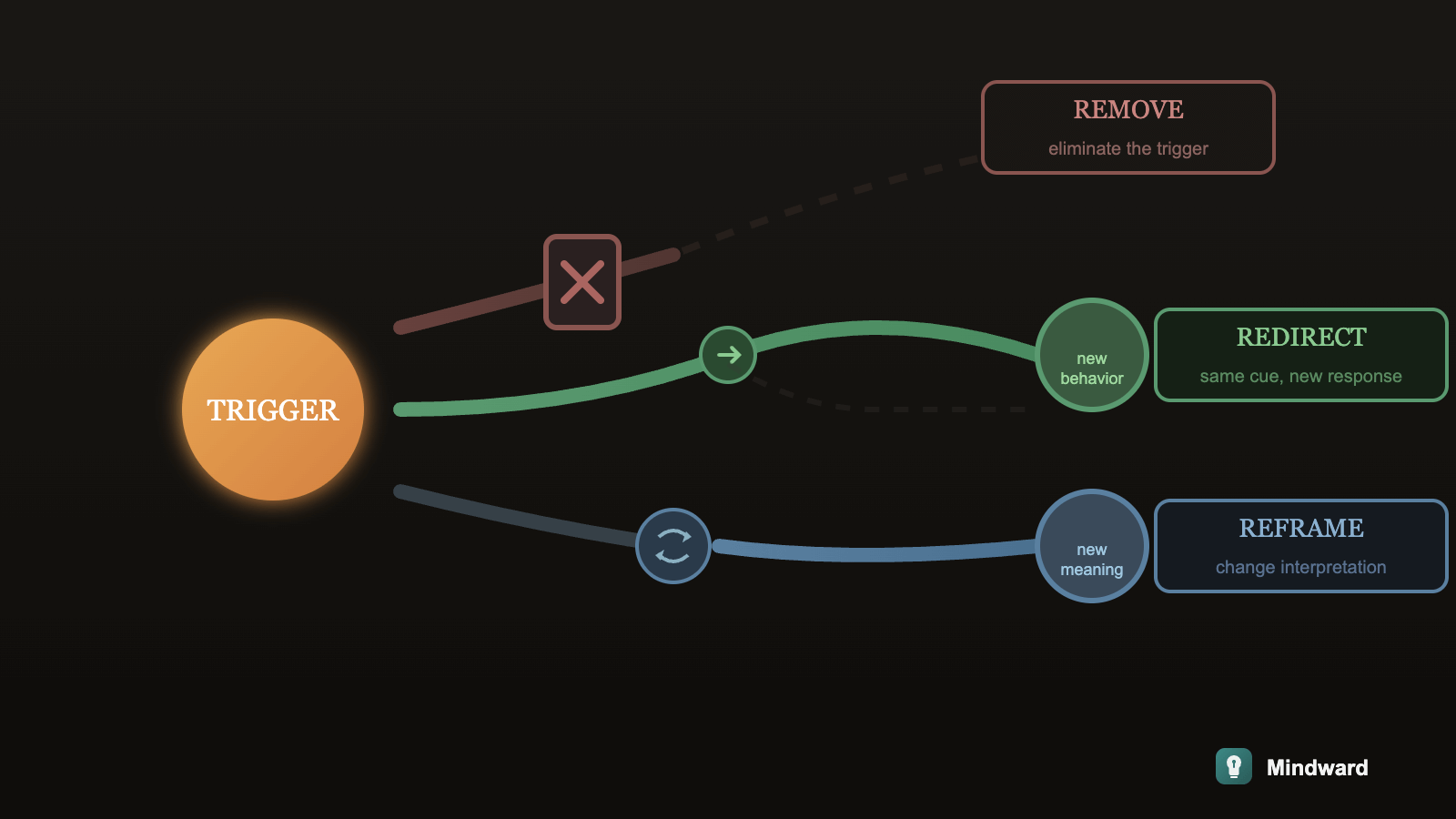

Once you've identified the trigger, you have options. You can remove it, replace it, or reframe it. Each approach changes the equation.

Removing the trigger means making it harder for the cue to appear. If your phone triggers scrolling, leave it in another room. If a certain route home triggers fast food, take a different route. If certain people trigger drinking, limit exposure.

Replacing the trigger means keeping the cue but changing what follows. If stress triggers snacking, replace the snack with a walk. If boredom triggers scrolling, replace the scroll with a book. The trigger still fires, but it leads somewhere different.

Reframing the trigger means changing how you interpret the cue. If the urge to check your phone is a trigger, reframe it as a cue to take a breath instead. The sensation stays, but its meaning shifts.

Why This Works Better Than Willpower

Willpower is a downstream solution. It tries to stop the behavior after the trigger has already fired. That's fighting uphill—possible, but exhausting and inconsistent.

Addressing the trigger is an upstream solution. It prevents the fight from starting in the first place. You're not resisting the urge; you're avoiding the conditions that create it.

This is why environment design beats motivation. It's why systems beat goals. The best strategy isn't to get better at resisting—it's to need less resistance in the first place.

Building Better Triggers

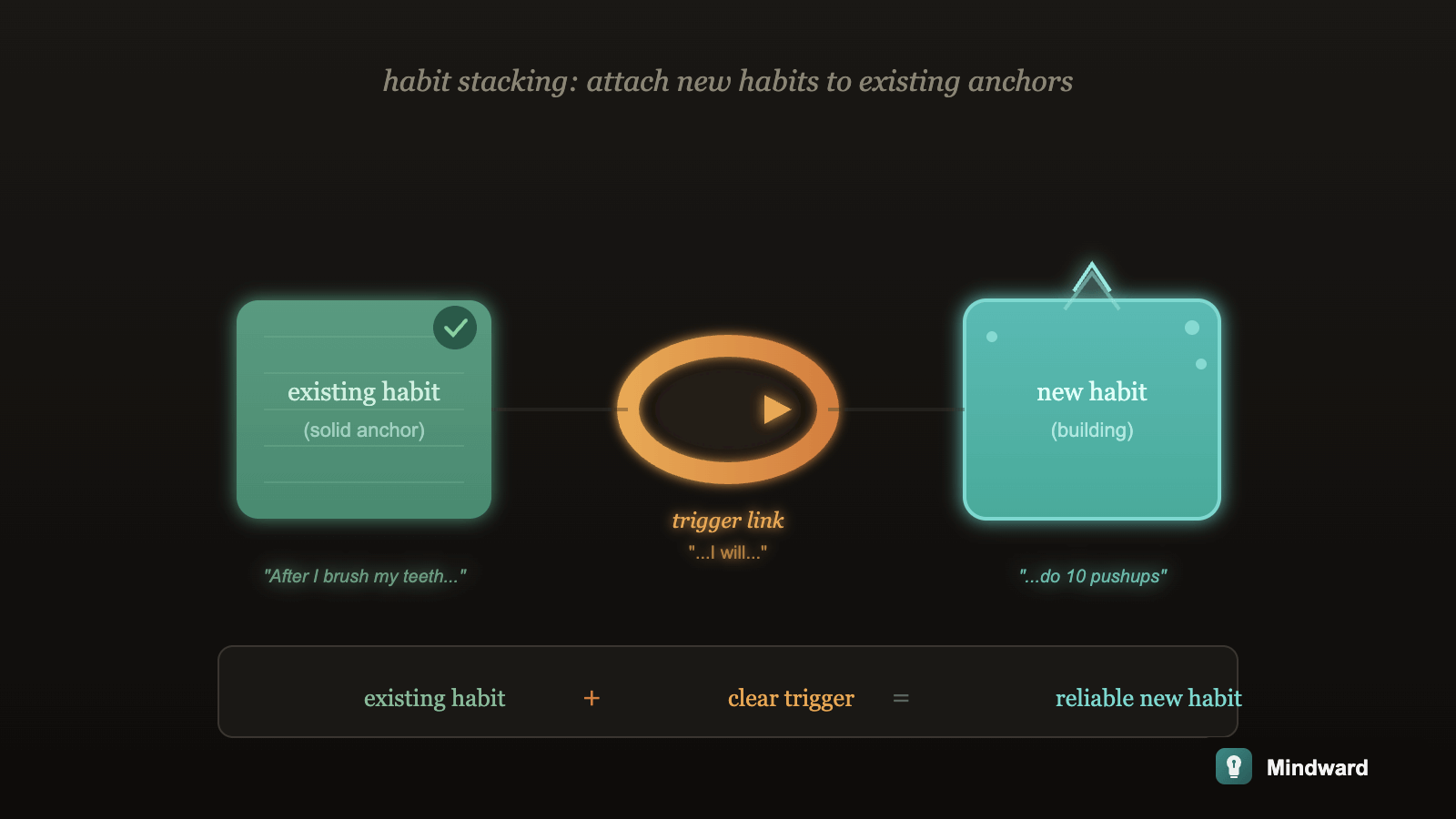

The same principle works in reverse for habits you want to build. If you're struggling to exercise, don't rely on motivation. Create a trigger—lay out your workout clothes the night before, link exercise to your morning coffee, schedule it immediately after another consistent behavior.

Good habits need clear cues. If the trigger is vague ("I'll work out more"), the habit won't stick. If the trigger is specific ("After I brush my teeth, I do ten pushups"), the behavior has something to attach to.

The Real Failure Point

When habits break, the instinct is to blame yourself. Not disciplined enough. Not committed enough. Not trying hard enough. But discipline isn't the bottleneck.

The failure point is almost always upstream—in the environment, the cue, the trigger that set everything in motion before you even realized it.

Stop trying to be stronger than your triggers. Start making your triggers work for you instead of against you.

Find the trigger. Change the trigger. The habit follows.

Comments

How did you like this article?

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!