Learning Doesn't Slow Down With Age. Your Approach Does.

Kids aren't better learners. They just learn differently—with immersion, play, and zero self-judgment. Adults can access the same conditions if they stop treating learning like work.

At some point, you started believing you were past your learning prime. Languages, instruments, technical skills—these feel like they belong to the young. You watch children absorb new abilities effortlessly while you struggle to remember a few vocabulary words. The conclusion seems obvious: the brain slows down with age.

But this isn't quite true. Neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to form new connections—continues throughout life. Adults learn differently than children, but not worse. The real gap isn't biological. It's circumstantial, psychological, and entirely addressable.

Children Don't Learn Faster. They Learn Longer.

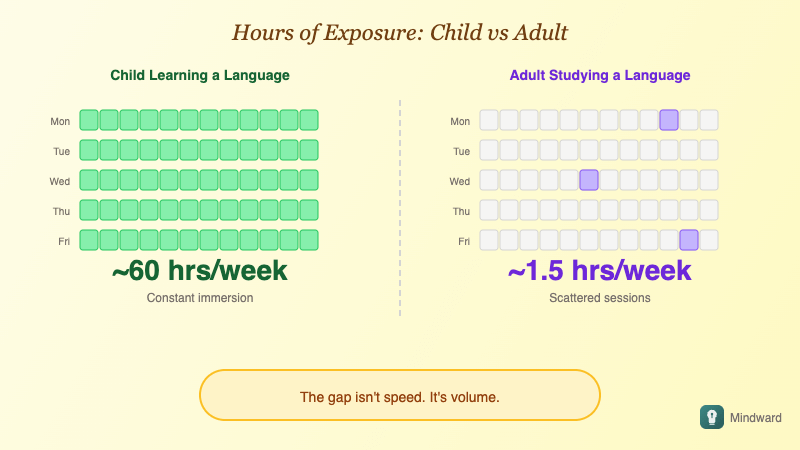

A child learning their first language is immersed in it for thousands of hours before they speak fluently. They hear it constantly, practice it in every interaction, and have no alternative way to communicate. When we say children learn languages easily, we're ignoring the sheer volume of exposure and practice they accumulate.

Compare this to an adult studying a language for thirty minutes a day, three times a week. The adult isn't learning slower—they're learning less. Hours of immersion versus hours of study aren't comparable. If adults logged the same exposure time as children, the gap would narrow dramatically.

The Curse of Self-Consciousness

Children practice in public without shame. They mispronounce words, draw badly, fall off bikes, and try again without attaching meaning to their failures. An adult beginner carries something heavier: the expectation of competence. You're used to being good at things. Being visibly bad at something feels exposing.

This self-consciousness changes behavior. Adults avoid practicing where others can see. They wait until they're good enough to perform, which means they never get the repetitions needed to improve. The ego becomes a barrier that children simply don't have yet.

Children aren't braver learners. They just haven't yet learned to be embarrassed by incompetence.

Adults Want Efficiency. Learning Wants Play.

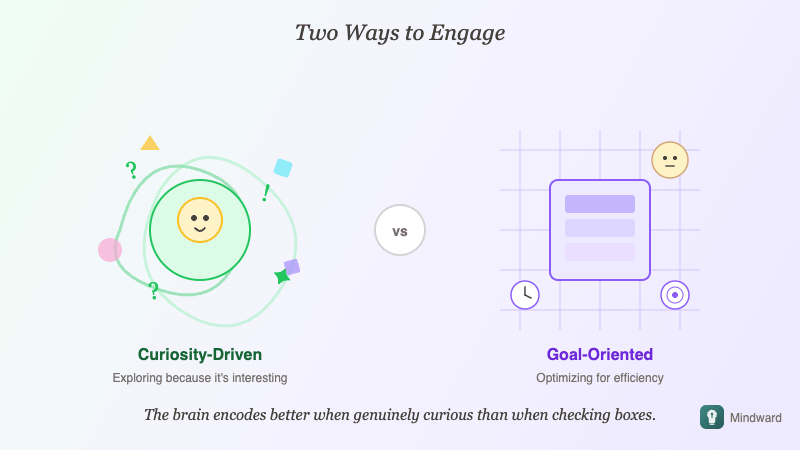

Adults approach learning like a project—structured, optimized, goal-oriented. You want the fastest path from not-knowing to knowing. You research the best methods, buy the right tools, create a schedule. This feels responsible. It's also often counterproductive.

Children learn through play—unstructured, curiosity-driven, intrinsically motivated. They're not trying to learn efficiently. They're exploring because it's interesting. This playful engagement activates different neurological processes than dutiful study. The brain encodes information better when it's genuinely curious than when it's checking boxes.

The Tolerance for Not-Knowing

Children live in a state of not-knowing. They're surrounded by things they don't understand, and this is normal to them. Adults have spent decades building competence. Not-knowing feels like regression—like something is wrong. This discomfort drives adults to quit early or avoid starting altogether.

Learning requires sustained tolerance for confusion. The period where nothing makes sense isn't a sign you're failing—it's the necessary first phase. Children tolerate this naturally because they have no alternative. Adults have to choose it deliberately, despite every instinct telling them to return to territory where they feel capable.

Competing Demands

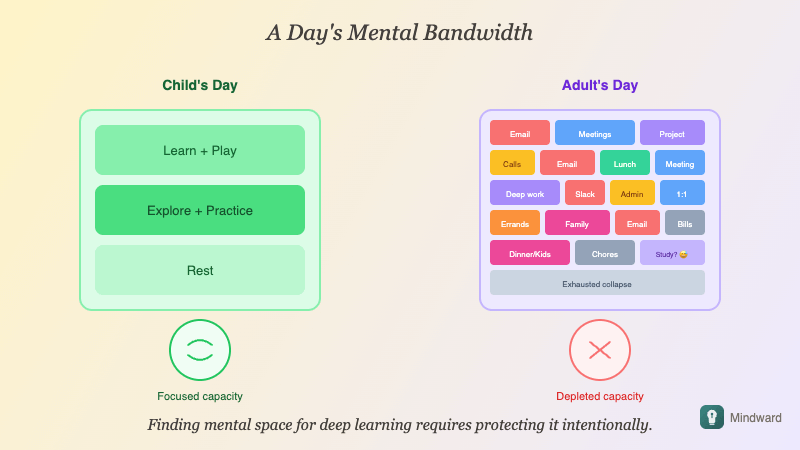

A child's job is to learn. An adult's attention is fractured between work, relationships, responsibilities, and the cognitive load of managing a complex life. Finding the mental space for deep learning requires actively protecting time and energy—something children get by default.

This isn't an excuse, but it's a real constraint. Adult learning requires more intentional design: blocking time, reducing distractions, and accepting that progress will be slower per hour simply because fewer quality hours are available. Comparing yourself to someone with no mortgage and no meetings isn't useful.

What Adults Actually Have Going for Them

Adults bring assets children lack: context, pattern recognition, self-direction, and the ability to understand why something matters. An adult learning music can draw on years of listening. An adult learning a language can use their knowledge of grammar, cognates, and learning strategies. Prior knowledge is scaffolding that children don't have.

Adults can also choose what to learn based on genuine interest and relevance—powerful motivational advantages over a child forced to study whatever school assigns. Motivation matters enormously for retention and persistence. Choosing your curriculum is an underrated adult privilege.

You're not past your prime. You're learning under different conditions than you did at ten—and you can change more of those conditions than you think.

The belief that learning belongs to the young becomes self-fulfilling. It leads to less practice, more self-judgment, and quicker abandonment when progress feels slow. But the brain remains capable. The real question isn't whether you can still learn—it's whether you're willing to be a beginner again, with all the awkwardness that entails.

Comments

How did you like this article?

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!