You Talk to Yourself in Ways You'd Never Talk to Anyone Else

The voice in your head says things you'd never say to a friend. That cruelty isn't making you better—it's keeping you stuck.

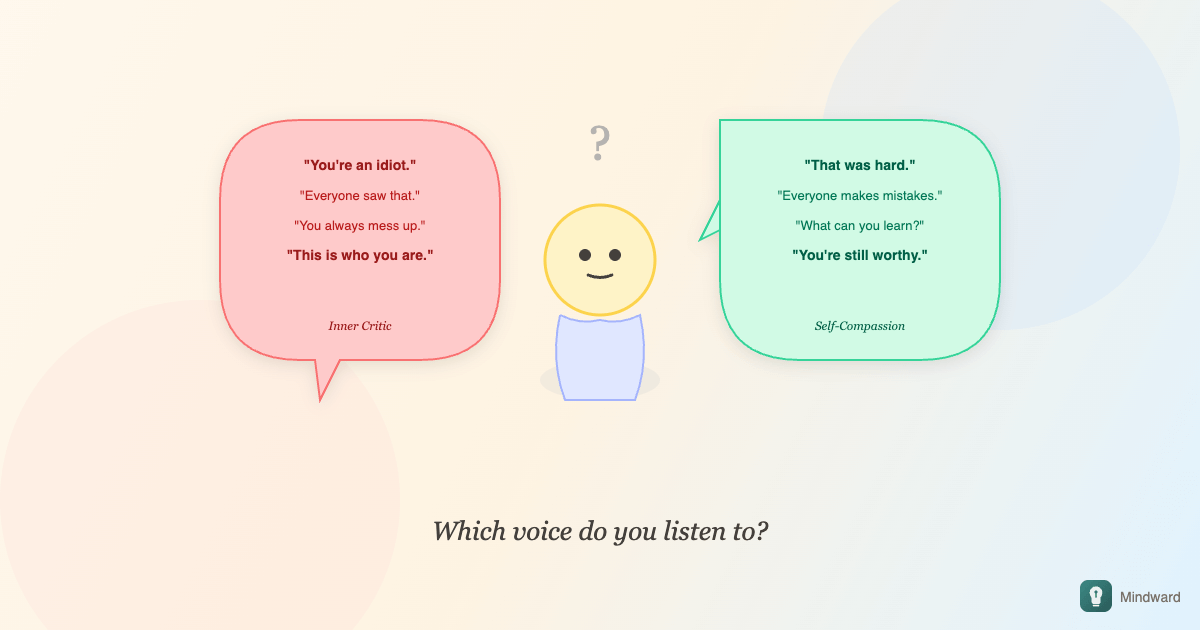

You make a mistake at work and the voice arrives instantly: You're an idiot. How could you be so careless? Everyone saw that. You're going to get fired. This is who you really are. The voice is fast, certain, and brutal. It speaks in a tone you would never use with another person—not a colleague, not a friend, not even a stranger.

Most people believe this voice is keeping them in line. That without it, they'd become lazy, arrogant, or mediocre. The cruelty feels like discipline. But research shows the opposite: the harsher your inner critic, the more likely you are to procrastinate, avoid risks, and stay stuck. The voice isn't helping. It's holding you hostage.

Where the Voice Comes From

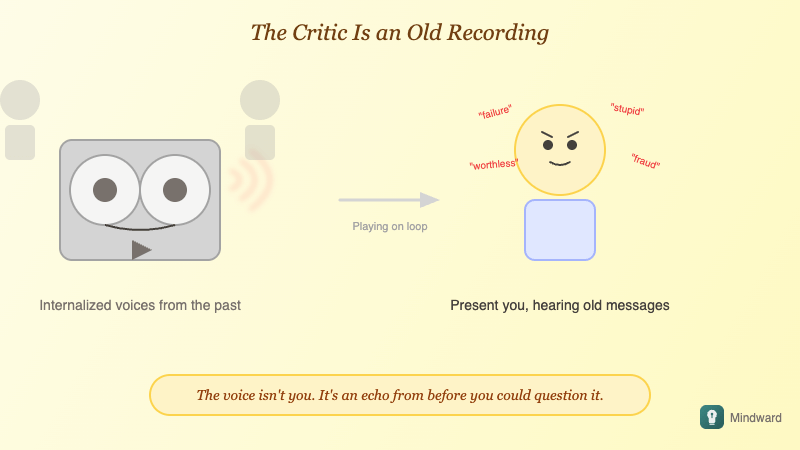

The inner critic isn't your authentic self. It's an internalized amalgamation—parts of parents, teachers, peers, and culture that you absorbed before you had the ability to question them. It speaks in absolutes because that's how children process the world: all good or all bad, success or failure, worthy or worthless.

At some point, you started believing this voice was you. But it's not. It's an old recording, playing on loop, responding to adult situations with a child's understanding of consequences. The stakes it describes—total rejection, complete failure, permanent inadequacy—rarely match reality.

The Cruelty Doesn't Work

There's a persistent belief that self-criticism drives improvement. Be hard on yourself and you'll try harder. But the data says otherwise. People with harsh inner critics are more likely to give up after failure, not less. They avoid challenges where they might fall short. They ruminate instead of problem-solve.

This makes sense when you think about it. If every mistake triggers a brutal internal attack, your brain learns to avoid situations where mistakes are possible. Risk becomes too expensive. Trying becomes dangerous. The critic designed to push you forward ends up keeping you frozen.

Self-criticism doesn't create motivation. It creates avoidance disguised as caution.

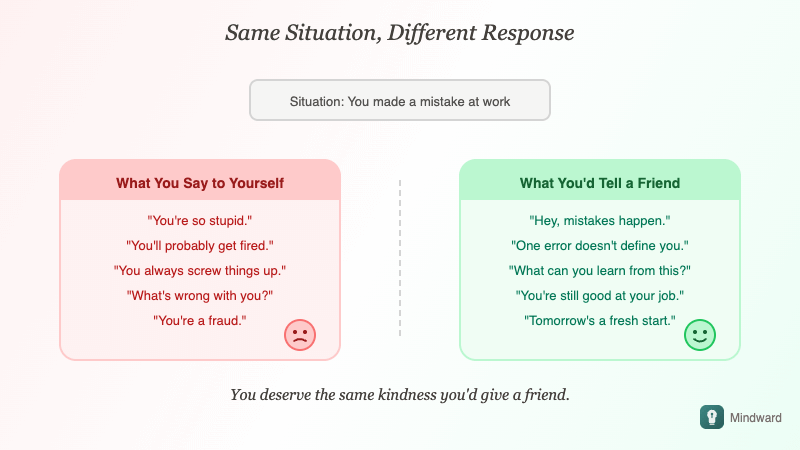

What You'd Say to a Friend

Imagine a friend came to you with the same mistake you just made. Would you say what you said to yourself? Would you call them an idiot? Tell them they're going to be fired? Suggest this one error reveals who they really are? Of course not. You'd offer perspective, remind them of context, help them see a path forward.

This isn't about being soft or avoiding accountability. It's about being effective. The way you'd talk to a friend—acknowledging the mistake while maintaining their basic worth—actually produces better outcomes. It allows for learning without shame spirals. It keeps the prefrontal cortex online instead of triggering fight-or-flight.

Self-Compassion Is Not Self-Indulgence

The fear is that being kind to yourself means letting yourself off the hook. That self-compassion leads to complacency. But self-compassion includes accountability—it just removes the cruelty. You can acknowledge a mistake, feel genuine remorse, commit to doing better, and still treat yourself as a person worthy of basic dignity.

Studies consistently show that self-compassionate people are more likely to take responsibility for their mistakes, not less. They don't need to defend, deny, or deflect because their self-worth isn't on the line. They can look clearly at what happened because looking doesn't threaten annihilation.

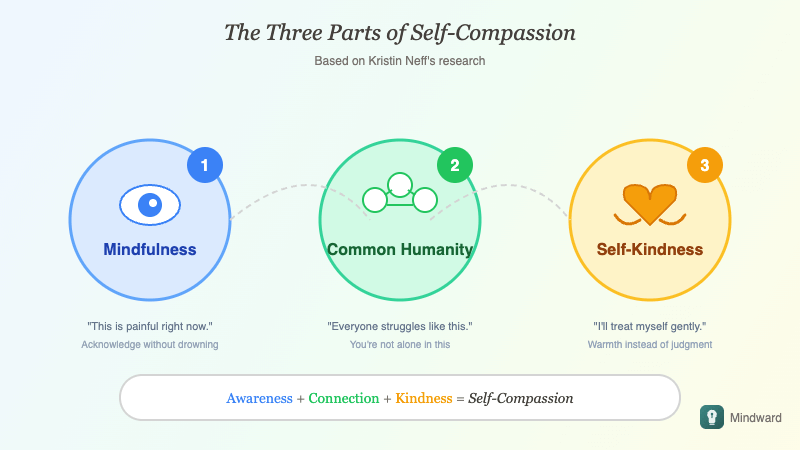

The Three Parts of Self-Compassion

Psychologist Kristin Neff breaks self-compassion into three components: mindfulness (acknowledging pain without over-identifying with it), common humanity (recognizing that suffering and imperfection are shared human experiences), and self-kindness (treating yourself with warmth rather than harsh judgment).

In practice, this sounds like: This is hard right now. Everyone struggles with things like this. What would I say to someone I care about in this situation? It's not about positive affirmations or pretending everything is fine. It's about responding to difficulty the way a wise, caring person would.

Noticing Without Believing

You can't always stop the inner critic from speaking. But you can change your relationship to it. Instead of I'm such an idiot, try: I'm having the thought that I'm an idiot. This small shift creates distance. The thought becomes something you're observing, not something you are.

With practice, you start to recognize the critic's patterns—when it shows up, what triggers it, the specific phrases it uses. It becomes predictable, almost boring. Oh, there's that voice again. It still speaks, but you stop treating its pronouncements as truth.

The goal isn't to silence the critic. It's to stop letting it run your life.

The voice will probably always be there to some degree. It's been with you for decades; it won't disappear overnight. But it can become quieter, less automatic, easier to question. And in the space that opens up, a different voice can emerge—one that sounds more like how you'd talk to someone you actually care about. Including yourself.

Comments

How did you like this article?

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!